Robots in everyday life

Despite the hype about the new types of robots that focus on caretaking, household tasks, and social interaction, there are only few robots in the everyday life of ordinary Japanese people. In the techno-orientalist view, someone who have not visited Japan, may believe that the streets are full of machine-like humans, or at least that all sorts of technological devises are used in households and offices.

The closest I got to this kind of vision was an advertisement in the subway train for the robotic vacuum cleaner Roomba (-which is in fact an American product!). This ad is clearly targeted towards housewives: the pink colours of the text and the carpet (-this image appeared during sakura season) and the elegant design of the intelligent household equipment, as well as the text, which reads: “Because it is spring and you want to go out, why not leave the cleaning to Roomba?” After promising a dust removal rate of 99.1 %, the ad presents the slogan: “Instead of you. As good as you. The robot does the cleaning”

Robotics on spectacular display

Robot Suit for the Future. International Symposium on Cybernics 2011, organized by Center for Cybernics Research, University of Tsukuba, at The Grand Hall, Tokyo, March 8-9, 2011.

Headed by Sankai Yoshiyuki, Professor at University of Tsukuba and President and CEO of CYBERDYNE Inc., this two-day symposium focused on the development of cybernics, an interdisciplinary academic field covering cybernetics, mechatronics and informatics with the goal of supporting a healthy society with citizens of old age and at good health.

Headed by Sankai Yoshiyuki, Professor at University of Tsukuba and President and CEO of CYBERDYNE Inc., this two-day symposium focused on the development of cybernics, an interdisciplinary academic field covering cybernetics, mechatronics and informatics with the goal of supporting a healthy society with citizens of old age and at good health.

Professor Sankai is the leader of a number of research programs supported by several Japanese ministries as well as the Cabinet Office, and the symposium brought together many of Professor Sankai’s international partners from Germany, USA, Italy, Sweden and Denmark, as well as his research collaborators in Japan.

Prominent in the symposium was the technology and application of the Robot Suit HAL (Hybrid Assistive Limb), a cyborg-type exoskeleton robot that is placed on the exterior of limbs on a human being. Small sensors placed on the surface of the skin can register brain signals to muscles in the particular limb, even if the muscles themselves cannot move (because of trauma, accidents or the like). By use of robotic technology, the bio signals will transmit to the exoskeletal machine, which will move the body part in question, hereby assisting the human being in moving. This technology can be used to enhance performance of the human body, such as helping disabled or elderly people to walk, or to carry out heavy-duty operations such as rescue work in disaster areas.

Prominent in the symposium was the technology and application of the Robot Suit HAL (Hybrid Assistive Limb), a cyborg-type exoskeleton robot that is placed on the exterior of limbs on a human being. Small sensors placed on the surface of the skin can register brain signals to muscles in the particular limb, even if the muscles themselves cannot move (because of trauma, accidents or the like). By use of robotic technology, the bio signals will transmit to the exoskeletal machine, which will move the body part in question, hereby assisting the human being in moving. This technology can be used to enhance performance of the human body, such as helping disabled or elderly people to walk, or to carry out heavy-duty operations such as rescue work in disaster areas.

Several models of the HAL robot suit were on display in the lobby of the sympoisum venue, and one of Professor Sankai’s female research assistants would talk around in the coffee breaks wearing the suit and take questions from visitors.

The symposium included visual display and demonstration of different types of HAL Robot Suits, and audiences of the symposium were invited to try on the robot suits for themselves. See video from the event by DigInfo News on YouTube.

Below is my own video from the symposium, emphasizing the spectacular performance of technology in the dramatic entrance of the HAL suits on stage. Members of professor Sankai’s research team acted as models. Because only a limited number of the audience could get to wear the robot suit HAL on stage, the host had to organize a lottery (-in the form of jan-ken-pon, ”rock-paper-scissors”).

This type of spectacular display of robot technology transgressed the boundaries for scientific events, as the show featured more as a mixture of fashion catwalk and rock star appearance (-with Professor Sankai as the leader of the band), rather than part of an academic conference. A large number of the audience, mainly young scholars, acted as groopies.

At the symposium, several papers focused on robot technology, while others specifically addressed medical issues such as neurosurgery or muscular dystrophy. Some papers had a sociological perspective on how assistive robots can be of benefit for various groups of citizens or institutions, as well as the measures to take when exporting or importing new technologies from Japan in terms of legal and financial issues. The presentations included papers on creative and visual dimensions of the design of technological objects such as robots, and how cybernetic embodiment can improve rehabilitation and enforce physical and cognitive abilities through creative play and imagination.

All in all, the themes of the presentations varied a lot, and despite the headlines of each section of the day, there seemed to be little coherence among the presentations. The so-called panel discussions at the end of each section contained little more than summaries of the presentations, and did not reveal much of an intellectual exchange among the speakers nor with the audience. Some of the presenters were not academic scholars, but representing government offices, who are involved in robot technology in one way or another. One example was Jesper Thomsen, Minister Counsellor and Deputy Head of Mission at The Royal Danish Embassy in Japan, who in an altogether praising tone mentioned a number of projects with Japanese robot technology already installed and taking place in Denmark. Thomsen at the same time invited more Japanese developers to test their technologies in Denmark because Danes are conceived of as “first movers” and the Danish society as very adaptable to new modes of operation and equipment.

Artistic and Scientific Collaborations

There are several examples of artists and robot scientists working together in the pursuit of creative elements of new technology with special attention to social aspects of human interaction with machines. One such example is the collaboration between the robotic scientist Ishiguro Hiyoshi from Osaka University with playwright and Artistic Director Hirata Oriza from Seinendan Theatre Company. Dating back from 2008, this collaboration so far has resulted in three performance works, two of which are mentioned below. Both performances were staged at the Tokyo Performing Arts Meeting (TPAM), which took place at various venues in Yokohama, 14-20 February 2011.

Nomura Masashi, dramaturg and Manager of Seinendan Theatre Company, explained at a seminar at TPAM that the question posed in the two plays is how robots and human beings can interact. The audience may perceive of the performance as a ”smooth” interaction between human and machine, or believe that robots can have emotions. In this way robot-human theatre is a sociological experiment. The performance is not supposed to lecture the audience, but point out various possibilities in the way in which humans interact with technology. At the same time, robot-human theatre also changes the notion of ”theatre” by challenging the convention that only human beings can act on stage.

さようなら / Sayonara is an Android-Human Theatre performance by Hirata Oriza, Seinendan, in co-production with Ishiguro Hiroshi, Osaka University & ATR Intelligent Robotics and Communication Laboratories. The play was performed by Geminoid F (android) and Bryerly Long (Seinendan) at Kanagawa Geijutsu Gekijô, 19 February 2011.

This short performance (15 minutes) features a female android placed in a chair on stage opposite a human actress, and the two act out a conversation as well as gestures and movements. Although the android has a realistic human appearance, and is dressed in female clothes and wears a wig, the performance does not hide the fact that the android is a machine. The point of the play is exactly the interaction between machines and humans. In this case, the woman, whose father bought the android for her when she was little, appears to be sick and perhaps dying.

The android robot recites poems for her, and the two talk about loneliness and happiness. When asked how it feels about these concepts, the android answers: “androids don’t know”. The woman says she think it was cruel of her father to buy the android for her because he knew she wouldn’t get well. The android asks: “Would you have preferred a more useful robot?” to which the woman answers: “No, it doesn’t matter anymore.” In the end, the android thanks the woman when she says: “I don’t think I will destroy you.”

働く私 / I, Worker is a Robot-Human Theatre performance by Hirata Oriza, Seinendan, in co-production with Ishiguro Hiroshi, Osaka University, and Kuroki Kazunari, Osaka University. The play was performed by Wakamaru (two communication robots by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd.), Nojima Mizuho (Seinendan) and Furuya Ryûta (Seinendan) at Kanagawa Geijutsu Gekijô, 19 February 2011.

Image of the two robots, cited from Seinendan website.

This 30 minutes performance is set in the near future in the home of the couple Mayama Yûji and Ikue, who have two robots, named Takeo and Momoko, to help out in the house. The robots are 1 m tall and have a bright yellow surface. The have a head and two arms, and they can move on wheels around on the stage floor. They have human voices and interact with each other as well as with the two humans. The robot Momoko is wearing a white apron.

The situation appears to be a normal everyday life, but during the performance the conversations and actions reveal a number of emotional aspects not only about the two humans, but also about the robots: Yûji has no work and does not like to go out of the house, while the male robot Takeo does not want to work (as a robot should). Momoko confronts Ikue that the couple does not have any children. The robot Momoko has become such a great cook that the only thing Yûji really enjoys, making food, is no longer necessary.

Other more subtle conflicts emerge, and the performance ends with the two robots alone on the stage. “You should never tell a human to buck up [ganbare] when they are depressed”, Momoko instructs Takeo, and he agrees: “Because we do not know what it is like to buck up.” The two robots discuss how to judge if the sunset is beautiful: “It looks pretty because you’re watching it with someone else”, claims Takeo, and the memory of watching it with someone else makes it equally beautiful. “I have no other way of understanding what is beautiful”, the robot says. “We are not yet that advanced.”

The issues addressed in these two stage productions are indeed very relevant and timely. In Sayonara, the physical appearance of the android as well as the apparent human dimension the robot takes on by reciting poems appropriate to the sadness of the situation, provided an insight into how future relations may play out. It poses an interesting question of how indeed robots can (or should) be programmed to respond to emotions. The android appeared as Other in terms of the stiffness and lack of overt gesture and movement, but the human being was also Other in terms of her ethnic background – a non-Japanese conversing in Japanese with the machine, and preferring that for the French that the android proposes they use.

In I, Worker the small size, the bold colours, and the cuteness of the two robots added an element of infantility that may be seen as a critical comment to the way in which many experience the Japanese society as being governed by childish or irresponsible behaviour.

See a short video from Reuters reporting on Sayonara, including short interview one-liners from Hirata, Ishiguro and Bryerly Long (the human actor)

The two performances do not give any easy answer to the interaction between robot and human being. However, the conflict is embedded in the content of the play, and therefore does not really challenge the concept of theatre, such as Nomura Masashi claims. Robots and human actors alike follow a script: the robots’ actions are programmed and their lines pre-recorded and played back at predescribed moments, just as the human actors’ lines are learned by heart and recited on stage. Despite the initial excitement of seeing a real robot on stage (-and in acknowledgement of the technical difficulties the actual staging may have encountered), the roles of the robots could in fact have been played by human actors or dolls.

The robots do not act on their own, but are subject to human manipulation and control. Robots adapting signs of sensibility and affect, or appearing to be able to manipulate human beings through emotions, is a fiction, and in this respect Hirata’s and Ishiguro’s collaboration does not move much beyond the very first robot play, Karel Čapek’s work R.U.R Rossum’s Universal Robots, published in 1920, which also gave name to the device now known as robot.

This image, retrieved from Wikipedia, shows a scene from the 1921 stage production of Čapek’s play, in which the three robots to the right are played by human actors.

New perspectives on cyborg experience

An exhibition entitled Odani Motohiko Phantom Limb 1997-2010 (小谷元彦 幽体の知覚 1997-2010) was shown at Mori Art Museum from 27 November 2010 to 27 February 2011. The exhibition featured recent works by one of Japan’s young international artists Odani Motohiko. Through his sculptural works Odani investigates ephemeral sensations in the body as well as amorphous phenomena in nature, trying to address the essence of existence and give it a visual form. In several of his works, Odani applies mechanical devices and pieces of machinery as a way of investigating the boundaries of the human body as well as invisible aspects of pain and pleasure.

Odani Motohiko, photo of the work Fingerspanner, 1998. Cited from the exhibition website.

Odani Motohiko, photo of the work Fingerspanner, 1998. Cited from the exhibition website.

The notion of “phantom limbs,” prominent in the title of the exhibition, refers to lost body parts that still create embodied sensations, and hereby challenge perceptions of time and space. In his strangely distorted and uncanny yet aesthetically pleasing sculptures, photography and video works, Odani provides new understandings of cyborg identity.

Animal and Machine Transformation

At MOT (Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo) there was an interesting exhibition entitled Transformation (トランスフォーメーション) shown between 29 October 2010 and 30 January 2011 as part of the Tokyo Art Meeting. Curated by Hasegawa Yûko and Nakazawa Shinichi, the exhibition included 22 Japanese and international artists and artist groups with the focus on the relationship between human and non-human. A number of the art works deal with transformation between human and animal, while others address issues of the cyborg and the hybrid of machine and organism.

Sputniko!, Menstruation Machine, Takashi’s Take, 2010, cited from the exhibition website.

Sputniko!, Menstruation Machine, Takashi’s Take, 2010, cited from the exhibition website.

The exhibition included a ”Transformation Resource Archive”, edited by Research Lab for Anthropology of Transformation (変容人類学研究室).

Robots and the Arts exhibition 2010

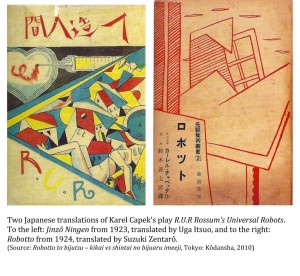

There is a strong interest among artists in the visual dimension of robots, especially the humanoid types that resemble human beings in one way or another. One example of the investigation of this visual impact is the exhibition entitled Robotto to bijutsu – kikai vs shintai no bijuaru imeeji / Robots and the Arts – Visual images in the 20th Century Japan (ロボットと美術 — 機械X身体のビジュアルイメージ) was shown several placs in Japan in 2010, and featured art works and other visual material related to robots from the 1920 publication of R.U.R. to present day androids and artificial intelligence.

The exhibition was structured chronologically, and displayed artifacts as well as photo documentation and art works related to robots. The first section introduced pre-robotic machines from before the concept of robot was established, including Edo-period (1600-1868) images of a mechanical doll that can serve tea. After the Japanese translation of R.U.R and the staging of the play in 1924, other visual versions of robots followed, among these Gakutensoku 學天則, a mechanical doll displayed in Kyoto in 1928. The futuristic visions of robot technology resonated well with Surrealism and Futurism in the 1920s and 1930s, and mechanical devises and technological drawings appear as elements in the works by several Japanese visual artists in this period, including Takayama Uichi, Kawabe Masahisa and Koga Harue.

Postwar images include artists, who design robots or create representations of imaginary robots, such as manga artists and figyaa (figure) designers. This section included original images of famous and well-known manga robot characters, including works by Tezuka Osamu, the inventor of Tetsuwam Atomu 鉄腕アトム (a.k.a. Astro Boy) in1951, and Yokoyama Mitsuteru, the inventor of Tetsujin 28 gô 鉄人28号 (Iron man no. 28) in 1956. Several showcases displayed a number of plastic figures created as models of popular manga characters, or as individual art works in them selves.

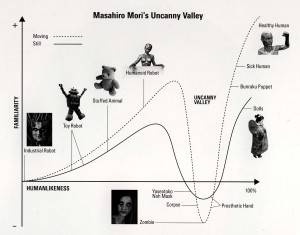

The display also included a number of actual robots under development. The catalogue contains short essays in various topics, including one on “Kikai no joseitachi – robotto no seibetsu o megutte” (The female machines – on the sex of robots), and another on the concept of Uncanny Valley (Fukimi no tani不気味の谷).

Robots and Visuality

Various robotic theories relate to vision and visuality. Japanese robotics Mori Masahiro, for example, coined the “uncanny valley” hypothesis in 1970, which links to Freud’s concept of Das Unheimliche. According to the hypothesis, when human beings see a robot, they are likely to have emphatic feelings for the robot only to a certain extend, after which repulsion take over.

Another example is the recent development of “partner robots” that rely on the robot’s visual sensing technologies in order to identify and recognize their human partner. These and similar theories point out the importance of sight and visuality to the ontology of robots – what defines a robot in terms of appearance, how and what can a robot ”see”, and how does the visual appearance influence human notions of robots?

Etynomology of Robot

The word “robot” derives from robota, the Czech (and other Slavic languages’) word for “work” or “labor”. The word “robot” was first used in the Czech writer Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), published in 1920. A translation into Japanese was published in 1923 under the title Jinzô ningen 人造人間 (Artificial human beings), and was staged under that title by the theatre company Tsukiji Shôgekijô in 1924. Another translation into the Japanese appeared in 1924 with the word Robotto ロボット (Robot) as the title.

Karel Čapek’s novel R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) from 1920 presents an image of robots who try to take control over human beings (-although the robots don’t succeed in the play). Anxiety about relationship between technology and humans often appears as a central theme in the scientific field of robotics as well as in popular culture.

The scientist and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov formulated three basic ethics for robots that will secure the survival of human beings:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey any orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Watch this YouTube video with Asimov himself explaining the Three Laws of Robotics:

The Three Laws of Robotics are still relevant – current issues concerning the design of robots for use in war deal with whether or not war robots obey the First Law of not injuring a human being. Some argue that robots can be programmed to act more “human” and ethical in tense war time situations than human soldiers.

Techno-Orientalism

Media outside Japan often report on the latest development in Japanese robot technology, and contribute to an image of Japan as a robotic nation. This may result in claims concerning Japanese people as more positively minded toward mechanical or electronic machines in their everyday life compared to other nations. Such perceptions are linked to the concept of Techno-Orientalism, in which Japan is constructed as the stereotype “Other” by the West because of the alleged fear of Japan as the “future” that transcends and displaces Western modernity.

The myth of the Japanese as “the most machine-loving people in the world” can be traced back to the 1970s at a time when Japanese industry and consumer products entered the international market and caused equal amounts of admiration and fear from the West. David Morley and Kevin Robins discuss in their book Spaces of Identity. Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries (London: Routledge, 1995) how new technologies have become associated with the sense of Japanese identity and ethnicity. They describe the concept of “techno-orientalism” in gendered terms as they suggest that technology has been central to the “potency” of Western modernity. The functioning and the significance of technology have been crucial for Western identity and, therefore, Japan’s advancement in the area of new technology during the 1960s became a challenge for the West. Morley and Robins argue that the West fears that “the loss of its technological hegemony may be associated with its cultural ‘emasculation’”. (Morley and Robins, Spaces of Identity, p. 167)

The critic and media activist Toshiya Ueno relates Techno-Orientalism to Orientalism as follows:

“The basis of Orientalism and xenophobia is the subordination of others in various areas of the world through a sort of ‘mirror of cultural conceit’. A host of stereotypes appeared when binary oppositions — culture and savage, modern and pre-modern , and so on — were projected on to the geographic positions of Western and non-Western. The Orient exists in so far as the West needs it, because it brings the project of the West into focus.” (Toshiya Ueno, “Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism”)

My research project on the cultural dimensions of robots will include questions about whether such Techno-Orientalist notions of Japan as “robot nation” still exist today, fifteen years after Morley and Robin’s book, or if the discourse has changed due to broader perspectives of globalization.

Robots in Japan

Japan is considered the world’s leading robotic country, and about one third of all robots around the globe are to be found in Japan. Robot technology is associated with economic growth because of the importance of industrial robots and service robots in the Japanese society, especially in the era of economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s.

NHK, the Japanese national broadcasting company, showed a program on January 11, 2011, which focused on ”the Japane Syndrome”, namely the problem of an aging population combined with declining birth rates. The share of elderly in the Japanese society is rising, and the traditional social structure based on extended families, where yonger generations look after the elderly, is rapidly changing. The Japanese government is therefore aiming at developing caretaking robots as a new area of growth, and supports the development of different types of humanoid and virtual robots for the purpose.

In the television program, robots were seen as the resource for the future that will save Japan’s economy because Japan’s technological know-how and experience on the field is coveted by several countries. Among those are Denmark and other Scandinavian countries because here, too, future problems are foreseen in regards to high numbers of elderly as well as high level of tax. The Danish ambassador to Japan, Franz-Michael Skjold Melbin, gave an interview in which he spoke about concrete plans of Denmark to join a collaboration of testing Panasonic’s new ”robot bed”. The ”robot bed”, apart from converting from bed to wheel chair and back, also makes use of it-technology which enables the user to watch television, go on the internet, and communicate with other people in the house from the bed/chair.

See a video of the Panasonic ”robot bed” from IDG Network.

At the same time as the number of elderly in the society grows, more and more women in the Japanese society opt out of the traditional role of motherhood, and either postpones or refuses marriage and children. According to the American anthropologist Jennifer Robertson, the Japanese government has launched a comprehensive plan, Innovation 25, which among other things contains ideas of developing more robots to take care of the “boring” tasks of home making in order to get more young females to choose the housewife role again. Read the article “Gendering Humanoid Robots: Robo-Sexism in Japan” and other articles on robots on Jennifer Robertson’s website.

Robertson refers to this illustration, taken from the website of the Japanese government Cabinet Office, presenting Innovation 25.

The image is accompanied by the following text:

“A society with diverse human existence

Rather than spreding telework, we wish to spred a lifestyle where you can work at home while raising children.

Rather than artificial intelligence, we promote possibilities of reducing time for housework and childraising and have more time for yourself.”

**

Research in Japan, spring 2011

My research project in Japan in the spring 2011 will focus on visual robot culture: what does a robot look like? Why do so many Japanese robots look like human beings? How do robots see? It is true that Japanese people have a more friendly and relaxed relationship to robots that people in the West? And if so, what are the reasons behind? How can art projects express a critique of such “positive” approach to robots?

A robot on display at Expo 70, the international world exposition in Osaka in 1970, where robots was a huge and popular topic for the 60 million visitors.

A robot on display at Expo 70, the international world exposition in Osaka in 1970, where robots was a huge and popular topic for the 60 million visitors.